Tianqi Wang

Evolutionary biologist

I’m an evolutionary biologist, which means I study how living things evolve to adapt to their environments! My research focuses on the fast evolution of guppies (small fish) in Trinidad.

My story

Me as a child in 2007

I grew up in northern China and lived there until I was 18 years old. My home was surrounded by diverse natural landscapes, with mountains just a 30-minute drive away and the sea accessible within 1.5 hours by train (which is very close by Chinese standards!). This allowed me to experience a wide range of nature and observe different wild animals from a young age.

In my early childhood, which was a time before touch-screen mobile phones but after the rise of televisions, I often entertained myself with documentaries about our planet, the mysterious dinosaurs, and the circle of life in Africa after finishing my homework. Those documentaries sparked my fascination with the natural world. Consequently, I frequently asked my parents to take me to the local zoo, though they would often try (unsuccessfully) to get me interested in the nearby botanical garden instead. Coincidentally, I also kept guppies as pet fish at home, primarily because they were the easiest to care for. Along with the guppies, I had three turtles.

On location during summer study in 2019

Secondary education back at home, from age 12 to 18, was incredibly intense. During high school, I joined in the Biology Olympiad, which aligned perfectly with my interest in animals and science. Looking back, I realize that the Biology Olympiad, which was largely based on undergraduate-level knowledge, probably made my university life slightly easier and gave me more free time to explore practical lab work and other interests beyond biology.

I completed my bachelor’s degree in Biological Sciences at Zhejiang University in Hangzhou. It is a famous tourist city in southern China, with completely different scenery, food, dialect, and lifestyle compared to my hometown. I had some great opportunities exploring the intertidal zone near the city, climbed Mountain Huang in a neighbouring province, and even travelled to the Alps in Germany and Austria during the summer of 2019.

Volunteering In a children’s library as part of my undergraduate, in 2019

Those four years gave me the opportunity to explore different subfields of biology and try lab research. My lab work included identifying bacterial species in seahorses and studying mitochondrial genes in crabs. Although neither project is directly related to my current research, both experiences were invaluable in teaching me how to work as part of a research team and develop my ability to think independently as a scientist.

During my undergraduate years, I also made friends with people who had diverse interests. My classmates have since gone on to pursue a wide range of careers in fields such as zoology, botany, disease research, cellular biology, biotechnology, and even areas outside of biology. Conversations with them encouraged me to reflect on my own passions and inspired me to explore my interests more deeply. Now I still love discovering new interests and devoting time and energy to learning about new things that bring me great joy and keep my curiosity alive.

My research

I’m an evolutionary biologist, which means I study how animals evolve to adapt to their environments (although it’s not limited to animals—evolutionary biology also examines the evolution of plants and microorganisms, which are vital parts of our planet. They help us understand why the world is the way it is today and what it might look like in the future!).

A Trinidadian stream, where guppies can be found

My research focuses on the fast evolution of guppies (small fish) in Trinidad. When most people think of evolution, they imagine dusty fossils, dinosaurs ruling the Earth, and changes happening over millions of years. But when I talk about fast evolution, I really mean it: the guppies in our study show obvious evolutionary changes within just 12 years! As a PhD student, I spend my time building mathematical models to understand how these guppies evolve in the wild streams of Trinidad, a tropical island in South America.

More about guppies

Guppies are small freshwater fish that, in Chinese, are called “peacock fish” because of their stunning tails. Like peacocks, male guppies use their colourful tails to impress females. As pets, guppies are often vibrant and showy, but in the wild, their colours are more muted due to limited food. While duller colours make courtship harder, they also help guppies avoid predators. However, this also makes them harder for researchers (like my colleagues and me!) to spot and catch during fieldwork.

Beyond their tails, guppies have another incredible trait—they evolve quickly! Researchers have observed that when guppies migrate (or are moved) from streams with large predators to safer streams, they can develop changes in body size, lifespan, and maturity within just a few decades. To test this, scientists relocated guppies from streams with large predatory fish to predator-free streams. Sounds like paradise, right? But is it really?

4 streams and millions of guppies

Measuring the canopy along a stream

Our research team has been studying guppies in Trinidad since 2008, way before I joined the lab. At the start of the project, researchers collected guppies from high-predation streams and put them into low-predation streams. (We don’t call them “no-predation” streams because another fish species, the killifish, lives there and can eat baby guppies until the young grow large enough to be too big for their mouths. On the flip side, guppies eat killifish babies too, so it’s fair game I guess.)

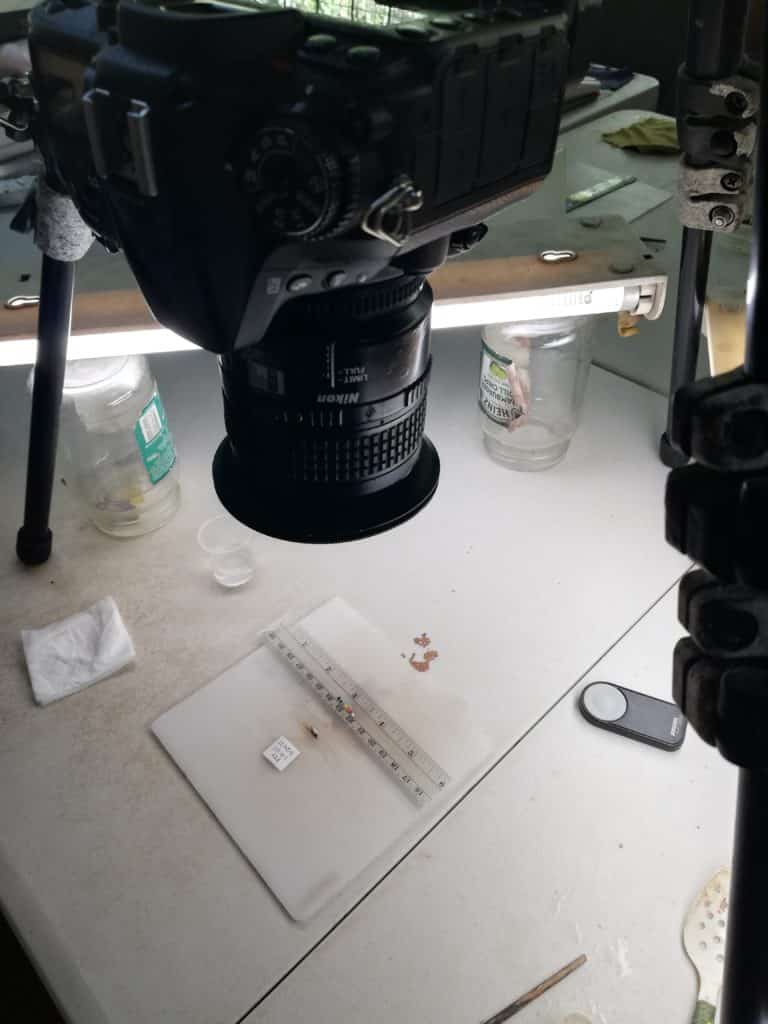

Since then, we have been conducting “mark-recapture studies”. This involves catching guppies using butterfly nets, which, in practice, means 5 or 6 researchers standing in a shallow stream trying to catch every guppy in a stretch about 100 meters long. Sometimes, we end up catching over 1,000 guppies in a single day! Once the guppies are caught, the next step is marking them. First, we anesthetize the guppies (which means put them to sleep for a short while) we have caught. Then, each guppy is weighed on a scale, and a photo is taken of it alongside a ruler to record its body length precisely.

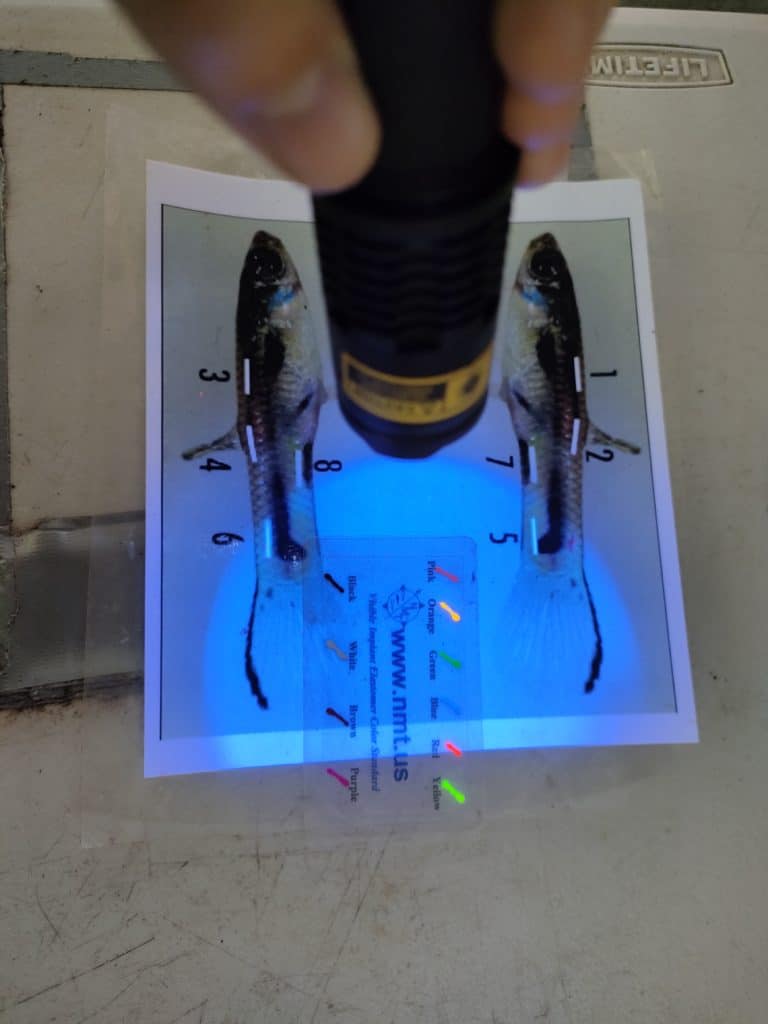

The trickiest part, however, is tattooing the guppies. While they’re still under anaesthesia, we inject a tiny amount of coloured dye under their skin at one or more of eight possible locations. With a combination of 10 different colours and these 8 positions, we can create a wide range of unique identifiers—far more than the number of guppies we actually have. If we catch a guppy that’s already been tattooed, we don’t need to repeat the process; we simply record the existing tattoo pattern to identify it. After marking, all the guppies are released back into the stream.

One month later, we return to the same location of stream and repeat the entire process: catching, marking, and recapturing the guppies. This allows us to track their changes over time.

Guppy marks observed under UV rays

This mark-recapture study began in 2008 and continued on a monthly basis without any interruptions until 2020, when COVID-19 reached Trinidad and disrupted our fieldwork. Over the 12 years of the study, we built up an incredible dataset: 144 months of data, 463,080 recapture records, and a total of 100,073 marked guppies.

Using this dataset, my role is to build mathematical models to analyse how guppies have evolved over time. While the modelling process might not sound as exciting as chasing fish in the wild (and honestly, sometimes it isn’t), it’s just as important for understanding what’s happening in these streams.

For example, by calculating the average body length of a guppy population in a stream and comparing that measurement across the 144 months, we can see whether guppies are getting smaller, larger, or staying the same from 2008 to 2020. (Spoiler: they evolve differently in different streams. In some, they get smaller over the years; in others, they grow larger. And in one surprising case, males and females evolved in opposite directions!)

Another question we can investigate is whether guppies are getting smarter and better at avoiding capture. (Spoiler again: they are, but only very slightly.) Analysing this requires highly complex models, and for streams with large populations, my computer has to work very hard—sometimes running for more than 24 hours straight to process a single model.

Taking a photo of a guppy (the fish is very small!)

By building these models, we can describe how guppies evolve without looking into their genetics, which is often the go-to method for evolutionary biologists thanks to technological advances. However, our work is far from complete. We still don’t know the exact causes of the changes we observe. Are they due to differences in the water, predators/competitors, food availability, parasites, or something else?

With more data collection and continued research, we hope to find the causes of Trinidadian guppies’ fast evolution and develop a better understanding of how the species adapt to their environments in real-time.